We left Springhill somewhere near the start of the August school holidays and couldn't move into our new farm at Waikanae for several weeks. So Mum and Dad rented a house at Waitarere Beach north of Levin. At least I think they rented it. I dimly recall Dad quickly coming to some arrangement with the landlord to pay for our stay by fixing the sewerage system. The house was on the beach front, and at least the beach was as big as a farm. We did things we'd never done before, like catching toheroa. If the toheroa season wasn't in the August holidays, then I've got my dates wrong. You would quietly walk along the beach at sort of low tide mark and look for a little indentation in the sand. It was like a finger print. Quickly you'd dig with your hands for about a foot, and if fast enough, you could grab the great four or five inch bivalve and pluck it out. If you stomped along the beach the toheroa would feel you coming and burrow down too deep to find. Once you had touched the toheroa, its tongue would hold itself in the sand so that you would have to pull with enormous force, and with a squelch at last it would surrender itself to your bucket.

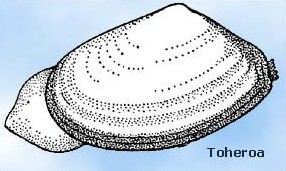

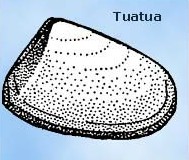

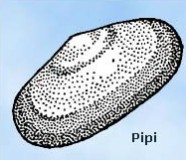

Mum made toheroa soup which was so beautiful that King George V or someone in nineteen hundred and something had asked for another plateful. "Until then, children," said Mother, "it was very rude to ask for a second helping of soup. Toheroa soup is very beautiful stuff, whether you like it or not - because the King said so". To be very clever and confuse the whole toheroa hunt, you could go on ahead and make tiny finger imprints in the sand. "There's one here, Mum," you would say. And Mum would excitedly dig to find nothing. "You made the mark with your finger!" declared Mum, looking tricked. And later when Mum went on ahead herself, you'd call out "Mum, I found one you missed!" and dig only to find you'd been tricked yourself. It was like eating a boiled egg as a child. After finishing you'd turn the eggshell over in the egg cup and call out, "Mum, you've forgotten to open my egg!" "Goodness!" laughed every mother since Eve, breaking off the top of the empty eggshell with the spoon, "You've tricked me!" But I digress. A toheroa, for the sake of any foreign reader, is like a big pipi or a big tuatua.

a silent stretch of sand, a twitching sponge, a shell, an abstract log with sand-worn spars projecting into the rising breeze. This is the beach. No longer was I going to be a simple biologist; I was going to be a marine biologist.     A few years later at the Hydrabad wreck with cousins Bear and Ray "Go and get a paper, dear" - or milk or bread or bananas. Never before had I being able to go to a corner shop without having to clean my face and get dressed up, with clean underwear and clean hanky, and travel for an hour in a car. On my first trip to the shop I saw a girl with no eyes. Her eyelids were sealed like clouds across suns, and I wanted to cut them open so she could see. "Why don't they just cut them open, with a razor blade? In a hospital?" For surely under every closed eyelid is an eye that can see. Yet she ran along the path to the shop as if she had eyes and I thought she knew I stared. But the path to the shop harboured something more sinister - something quite different. The path to the shop was the territory of a boy who would hide ready to leap out and bash you up. Back in Springhill there were no territories. Not even a farmer's fence was a boundary for children. Children were like flocks of turkeys who could cross boundary fences without a care and come under some sort of shared proprietorship. But here, at Waitarere, was a boy bigger than me who'd bash me up if I walked on the path to the shop. "Just ignore him," said Mum. I quickly learned to take the long way, and the joy of going to the shop soon lost its innocence. It was 1960. I was ten. It was my first venture into growing up. My world, for the first time, was divided into big people and little people. And the big people could do what they like. And often did. Return to the Previous Chapter Return Home Contact the Author |