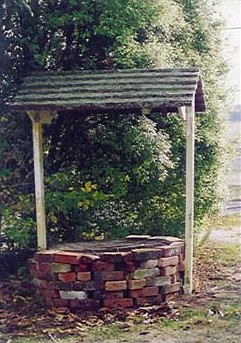

Mum wished for a wishing well. Our new house on the farm had a large garden, and Mum had seen a picture of a wishing well in The Auckland Weekly. It was the traditional English wishing well with rope, bucket and all. Dad seemed reluctant to make it, but with the school gala coming up Mum planned a plot. Why shouldn't Dad make a wishing well for the school gala? You could then toss a coin into the well, haul the bucket up on the rope and find a present in the bucket. "And, Frank," she said, "I have a picture of it here in The Auckland Weekly". When it was all done, of course, and the gala was over, the well could simply be shifted back home from school and stored in our garden. "Wouldn't that be lovely, dear?"  The Well Music boomed out on the old windup 78 record player. Mum bought a red and white checked table cloth, embroidered with white criss-crosses, made by Mrs Crystall's mother. For years that table cloth covered our dining table. And at the end, after the great clean up, with the stalls gone, and the truck gone, and the rubbish cleared, there sat Mum's wishing well in the middle of the school grounds.

Now Mum, who knew more things than us kids, said to us: "If anyone at school makes a speech or gives a farewell gift to Francie, Bruce and Leo, you must make a speech in reply." She wrote the speech out for Francie and me, and we learnt it off by heart. It was vague enough not to give the secret away. "Thank you for your kindness. We have enjoyed our time at Springhill and are sad to be going. We will miss you all." So Francie and I went around saying "thankyouforyourkindnesswehaveenjoyed ourtimeatSpringhillandaresadtobegoingwewillmissyouall" over and over until we knew it well. We knew we wouldn't have to use it because we couldn't think when. Even when Francie and I were sent out to the shelter shed to take the primers for reading - "And take your little brother," said Mr Allen - we didn't realize that the others were planning something. Even when Mr Allen said, "Today in class we are going to make colourful party hats," we didn't realize that the others were planning something. Even when the photographer arrived and lined up the whole school for a photograph, we didn't realize the plan. Nor when Francie and I went with some others down to the stream to catch some cockabullies for the class fish tank. "And why not have an extended lunch hour?" said Mr Allen. "Come back at two o'clock".

Everyone clapped, and waited. I nudged France. "Make the speech," I whispered. "No! You do it!" she whispered back. "No!" I said. "You do it!" "You do it!" "No!" We went home in great excitement. "Mum! Mum! Mum!" we shouted. "Guess what? They had a surprise party for us and we were given this picture and had cakes!" "Oh! How lovely, dear," said Mum. "And did you make the speech?" "Yes," said France. "She did it very well," I added, determined that Francie's reluctant reply would appear to come from a sense of modesty. She said "thankyouforyourkindnesswehave enjoyedourtimeatSpringhillandaresadtobegoingwewillmissyouall". "That's lovely, dear," said Mum. "At first," said me, warming to the occasion, "Francie was a bit scared. But then she stood up and said it". "That's lovely, dear," said Mum. And we went out to play while Mum continued to wrap the crockery in old Auckland Weeklies and pack them into large wooden crates. "Children! Come here!" called Mum, several hours later. "Mrs Leach just phoned and said that Pam said that Francie was too overcome to make a speech. You naughty, naughty, NAUGHTY children." Well, that kind of put a damper on the festivity. And several days later, all loaded up in the car, we still felt the sting. The cat, at the moment of departure, ran under the house and wouldn't come out. In the end, we drove off, down the long, long drive lined with oak and fir saplings that Mum had planted for a future time, and left the cat behind for Miss Swinburn on the farm next door to find and feed. It was a naughty, naughty, NAUGHTY cat.  The Gate It's lonely in a paddock.  Farewell Return to the Previous Chapter Return Home Contact the Author |