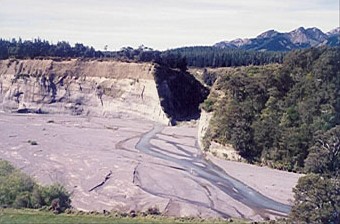

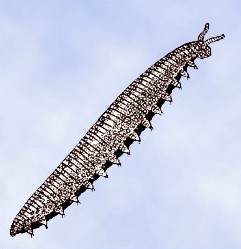

The thing about mountain rivers is that they can rise very suddenly. Mountains collect the rain and the rain fills the creeks and the creeks fill the tributaries and the tributaries fill the river and before you know it, even if it's sunny on the river bed, the river floods. This day, Cousin Bear and I went exploring up the Makarora River. The Makarora wound down from the Wakarara Ranges and somewhere downstream joined the Waipawa River. The Wakararas were bare topped and, except in mid-summer, snow-capped and riddled with shingle slides. The river had gorged deep ravines, and up the old track you would find sideless bridges made of old planks where years before the timber millers had crossed. Sometimes on a still day you could hear a roar coming from the mountains, and you knew within the hour there would blow a hot nor-westerly gale.  At Wakarara So we crossed the Makarora and climbed over this small spur to another river. This new river didn't have a name, so we named it after ourselves because we had discovered it on an earlier day. We called it the Bearruce River. Today we were on a peripatus hunt. A peripatus is a couple of inches of a caterpillar-looking thing that isn't a caterpillar and lives in damp logs and is a hang-over from dinosaur days. When you hold it in your hand it spits blue milk up your arm. Today schools teach all about Tyrannosaurus rex and Brachiosaurus and not about the dinosaur in our own back yard. Bear and I, at the age of eight, didn't read about dinosaurs, we hunted them. It would be a pity if, after 160 million years, Bear and I were the ones responsible for the extinction of the peripatus. It could well be a bit like our common grandfather, George Peers, who as a kid in the area, trapped huia birds to sell the tail feathers to local Maori. Anyway, armed with an old shoe box we crossed the Bearruce River in search of dinosaurs.  Peripatus Of course, eight year old boys don't simply go home with a peripatus in a shoe box. The Makarora River could well have a new eel, or a new rock, or a new route. So we followed it some way up stream. I forgot to mention that the spur we climbed was slippery, grey papa rock, and this grew into a high cliff upstream that banked the river. The papa cliff went straight into the clouds hundreds of feet high. So one side of the river was the small flat with the derelict mill town where only the Martins lived, and the other side of the river was the sheer papa cliff. Sometimes at night in bed, when the river flooded, you'd hear great pieces of the papa rock crashing into the raging river. Bear found an eel in a nook at the base of the cliff. Suddenly, we looked up to discover that the river was in flood and rising. We were trapped on a small piece of river bed between the raging river and the sheer papa cliff. Our piece of land was getting smaller and smaller. Smaller and smaller our piece of land got and higher the river. The water was a roaring dirty brown. A log swept past. The peripati set sail in the shoe box and headed for South America. We found a stick on our island, so we grabbed one end each, and faced with no choice, plunged into the torrent. Within seconds, our feet could no longer touch the bottom. We bounced along, with only our heads appearing, clutching the stick for grim death. The river bank opposite shot past at a hundred miles an hour. Then we were on the other side, emerging muddy and wet and safe. By now it was raining, and the tops of the Wakararas were shrouded in cloud. We set off home, crossing the small flat with the derelict mill town where only the Martins lived.  Me, Jane, Bear, Francie We never knew the Martins. Rumour had it that they had fourteen children. We never saw them. To see Mr Martin sitting on the dunny was rare. When we were climbing the hill to get home we were above Mr Martin's outhouse, and were seized by a sudden desire to chuck rocks on his dunny roof. Clunk! Clunk! Mr Martin appeared, doing up his pants, and shouting "Whatthexyoicurmtx cuziquedoyouthinkyouareklminztoff!" It was great fun. He couldn't catch us. Then a gun sounded. Pellets splattered around us. It was Mr Martin firing his shot-gun and still shouting "Whatthexyoicurmtxcuziquedoyouthinkyouareklminztoff!" We took off up hill. Bear slipped on the wet ground and rolled into me. We both fell, and rolled clutching each other. We rolled, and rolled, and rolled down the hill - all the way to Mr Martin's feet. "Whatthexyoicurmtxcuziquedoyouthinkyouareklminztoff!" We ran like hell. Back home, once warm and dry, we planned tomorrow. It's funny how parents never ask how come you got so muddy. Return to the Previous Chapter Return Home Contact the Author |